Introduction: Why Deferred Revenue Matters in SaaS M&A

If you’re a SaaS founder approaching ~$10M ARR and considering an acquisition, understanding deferred revenue can be critical. Not only is it an important accounting concept for running a software business, but it also plays a big role in how your company is valued and how purchase agreements are structured.

In this blog, I’ll explain in plain English what deferred revenue is and why it matters for SaaS companies. We’ll compare cash vs. accrual accounting (and why deferred revenue even exists), dive into multi-year contracts and Remaining Performance Obligations (RPO), and then explore how deferred revenue is treated in acquisitions. That includes if not structured correctly, the dreaded “deferred revenue haircut” and recent changes in accounting rules that affect it. I’ll also share strategies (with a couple of case-style examples) for how you, as a seller, can maximize your company’s value in light of these accounting treatments.

My goal is to make this accessible and actionable – by the end, you should feel more confident about this topic, and know when to seek expert advice to navigate it.

Explore our SaaS Exit Planning Overview for tips on preparing financials and avoiding common deal breakers.

What is Deferred Revenue (Unearned Revenue)?

Deferred revenue (also called unearned revenue) is money your company has received for services or products you haven’t delivered yet. In a SaaS context, this typically happens when customers pay upfront for a subscription or contract. For example, if a customer pays you $120,000 today for an annual subscription, you can’t count all $120K as revenue immediately – you haven’t earned it all yet because you still need to service the customer for 12 months. Instead, that $120K goes on your balance sheet as a liability called deferred revenue (or contract liability), and you recognize it as actual revenue on your income statement gradually over the subscription term. Each month, as you deliver the service, you recognize $10,000 as revenue, and the deferred revenue liability decreases on your balance sheet.

Think of deferred revenue as a promise your company has to fulfill. Until you’ve delivered the software service for the period paid, the money isn’t truly “yours” from an accounting perspective. This concept is rooted in basic accounting principles: under accrual accounting, revenue is recognized when it’s earned (when the service/product is delivered), not necessarily when cash is received. Deferred revenue accounts for that timing difference. It provides a more accurate picture of your SaaS company’s financial health than if you just recorded all cash receipts as immediate income. In the context of deferred revenue in SaaS acquisitions, this distinction becomes especially important for buyers evaluating long-term service obligations versus recognized revenue. In fact, deferred revenue is so common in software and subscription businesses that even giants like Microsoft report huge deferred revenue balances (e.g. Microsoft had over $60 billion in deferred revenue in 2024, reflecting massive future service commitments).

For SaaS founders, it’s important to grasp that deferred revenue isn’t “bad” – it’s a sign of success in selling subscriptions! It means customers have paid in advance, boosting your cash flow (often a welcome funding source for growth). However, it does require delivering on those services, and it makes your financial statements a bit more complex. Understanding deferred revenue helps you manage cash flow, forecast revenue correctly, and communicate with investors. As Investopedia puts it, recognizing deferred revenue properly ensures your financial statements reflect what your company owes (services to deliver) versus what it has actually earned. This transparency is crucial for planning and for maintaining trust with stakeholders.

Cash vs. Accrual Accounting: The Timing of Revenue Recognition

Let’s briefly contrast cash accounting vs. accrual accounting, because this is key to understanding deferred revenue.

- Cash-Basis Accounting: Revenue is recorded when cash is received. If you invoice a customer $120K for the year and they pay upfront, cash-basis accounting would show $120K revenue immediately (and $120K cash in the bank). Simple, but potentially misleading for a subscription business – it would make one month look huge and the following months look empty, even though you’re delivering service throughout. Cash accounting can distort the true performance of a SaaS business because it doesn’t match revenue to when the service is provided. This is especially relevant in understanding deferred revenue in SaaS acquisitions, where buyer expectations often rely on accrual-based statements rather than lump-sum views. For this reason, cash accounting is rarely used once a company grows beyond a very small operation. (In fact, GAAP and IFRS require accrual accounting for most companies.)

- Accrual Accounting: Revenue is recorded when earned (when the service or product is delivered), regardless of when cash is received. Using the same example, under accrual accounting you would recognize $10K of revenue per month over 12 months, not $120K all at once. The unearned portion sits on the balance sheet as deferred revenue. This gives a better sense of your company’s actual recurring sales and obligations, smoothing out that upfront payment over the period it is earned. Accrual accounting is considered more accurate for gauging business performance over time– especially for SaaS, where subscription revenue is earned continuously. It also aligns with the matching principle in accounting (matching revenue with the period it is earned and the expenses incurred to deliver it).

See how proper accrual reporting improves SaaS valuations

In short, deferred revenue only exists under accrual accounting. If you’ve been doing cash-basis bookkeeping, the concept might feel foreign – but as you prepare for an acquisition, you’ll need to ensure your financials are on an accrual basis (buyers and auditors will insist on it). This means mapping out all those upfront payments to the periods of service. The result is a balance sheet that shows a deferred revenue liability for any services you owe. Don’t worry: this is normal for SaaS and actually highlights the strength of having customers committed and paid in advance. Just remember, cash is collected upfront, revenue is earned over time.

Multi-Year Contracts and Remaining Performance Obligations

Many SaaS companies, especially enterprise-focused ones, sign multi-year contracts or subscriptions. For example, you might land a big customer on a 3-year agreement for $300K per year. How does this impact deferred revenue?

It depends on how you bill it:

- If you invoice the full $900K upfront and get paid, you’ll have a huge deferred revenue balance initially. After the first year of service, you’d have recognized $300K as revenue and still have $600K deferred for the remaining two years (often split into current and long-term deferred revenue on the balance sheet). Essentially, you’re sitting on a pile of cash that you will recognize as revenue over 36 months.

- If instead the contract bills annually ($300K each year), at the start you’ve only received $300K. You’d defer that $300K and recognize it over year 1. At the first anniversary, you bill the next $300K, and so on. In this scenario, your deferred revenue at any given point might just be the remainder of the current year’s payment, but you also have a contractual backlog for the future periods that aren’t billed yet.

This structure is especially relevant in SaaS acquisitions, where long-term contracts can affect valuation modeling and deferred revenue liability forecasts.

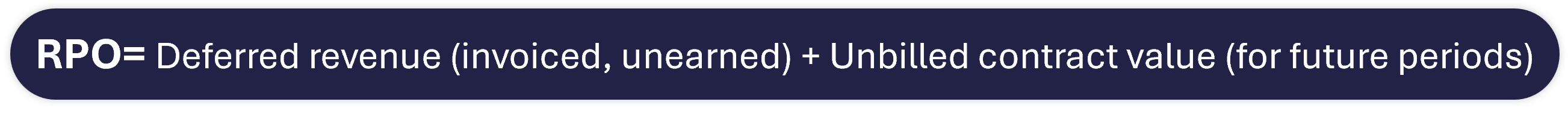

This brings us to Remaining Performance Obligations (RPO). RPO is a metric introduced by the revenue recognition standard (ASC 606 / IFRS 15) that represents the total value of contracted revenue that you haven’t recognized yet – essentially a sum of deferred revenue + contract backlog for signed contracts. In other words:

It’s an indicator of future revenue you are going to earn from existing customer commitments. Public companies are required to disclose RPO in their financial statements now, because it gives investors a clear picture of how much revenue is “in the pipeline” from signed deals.

For a SaaS founder, even if you’re not public, understanding RPO can be useful. It highlights the long-term commitments from customers:

- Deferred revenue is the portion of cash already collected for those commitments.

- Backlog (unbilled) is what you expect to invoice later under the contract.

For instance, if you closed that 3-year, $900K deal and got $300K upfront for Year 1, your deferred revenue would be $225K after Q1 (for the remaining 9 months of year 1), and your RPO might be $825K (the $225K deferred + $600K for years 2 and 3 not yet billed). RPO provides a more holistic view of future revenue than deferred revenue alone and can significantly influence M&A valuation for SaaS companies. It’s a great metric to track internally and to communicate to potential acquirers, because it shows the total contractual revenue stream that the business can expect, beyond just the ARR/MRR. High RPO relative to current revenue means you have a lot of revenue locked in going forward – a positive sign of stability and growth.

However, multi-year deals and high deferred revenue also introduce some complexity in accounting and, as we’ll discuss next, in acquisition negotiations. More money upfront is great for cash flow and reduces risk of customer churn (since they’re contracted), but it also means the accounting will carry larger deferred liabilities. Keep that in mind as you strike big deals in the run-up to an exit.

Deferred Revenue in Acquisitions: Fair Value and the “Haircut”

Now the crux of the matter: how deferred revenue is handled when you sell your company. This is where many founders get a crash course in purchase accounting and sometimes face an unpleasant surprise if they’re not prepared. I’ll break down the key concepts: purchase accounting fair value adjustments, the deferred revenue haircut, and how this plays out post-acquisition.

Fair Value Accounting for Deferred Revenue in Acquisitions (Purchase Accounting 101)

When a business is acquired, accounting standards (ASC 805 for GAAP, or IFRS 3 internationally) require that the acquirer re-measure the acquired company’s assets and liabilities at fair value as of the acquisition date. Deferred revenue accounting in acquisitions is no exception – even though it’s a liability representing future service obligations, the acquirer can’t just carry it at the same book value the seller had. Instead, they must assess the “fair value” of those obligations.

Fair value of deferred revenue is typically defined as the amount an independent party would require to assume the obligation of delivering the remaining service. In practice, acquirers often calculate this by estimating the cost to fulfill the remaining obligations plus a normal profit margin for that effort. This usually comes out to less than the deferred revenue’s book value, because the book value includes the profit margin that the selling company expected to earn. (This aligns with GAAP compliance in SaaS accounting) For example, if you have $800K of services left to deliver (book deferred revenue) and it will cost about $400K to actually deliver with a reasonable margin, an acquirer might record the fair value of that obligation at $400K.

The difference between the seller’s deferred revenue balance and this lower fair value is commonly called the “deferred revenue haircut.” It’s essentially a write-down of the deferred revenue liability (and a corresponding write-down of revenue that the acquirer will recognize later). This isn’t just theory and it was standard practice in tech M&A for years. As one valuation expert notes, fair value re-measurement “typically results in a significant downward adjustment (commonly referred to as a ‘haircut’) for technology companies — particularly those in software/SaaS”. Why? Because in SaaS, you often have high margins and upfront sales/marketing costs; once a contract is signed, the remaining cost to deliver the service (hosting, support, etc.) is relatively low. So, the fair value of the obligation (cost + a small margin) is much lower than the deferred revenue that includes your full margin.

Let’s illustrate with a simple case study (a hypothetical but realistic scenario):

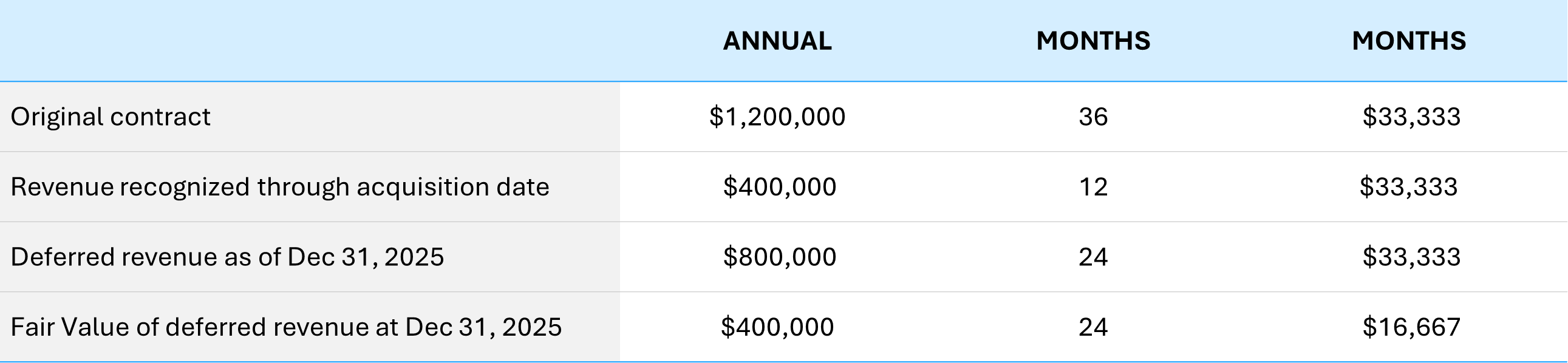

Case Study 1 – The Haircut in Action: SaaSCo signs a 3-year, $1.2M enterprise deal in January 2025. They collect the entire $1.2M up front. By end of 2025, they have delivered one year of service, so under accrual accounting $400K is recognized as revenue and $800K remains as deferred revenue on the balance sheet. Now assume SaaSCo is acquired on Dec 31, 2025. The buyer must record a fair value for that $800K deferred revenue. After analysis, they determine the cost to deliver the remaining 2 years of service is $400K, so they record $400K as the contract liability fair value. In other words, the buyer writes down half of the deferred revenue. This $400K difference is the “haircut” – it effectively disappears from the acquirer’s revenue schedule. Post-acquisition, the acquirer will only recognize $400K of revenue over the next 24 months from that contract, instead of the $800K the seller would have recognized if no acquisition occurred.

From the seller’s perspective, this seems odd – the cash was already received and the customer still expects service, so nothing has changed with the customer contract. But from an accounting standpoint, the acquirer can’t count revenue that essentially represents profit that the seller had locked in. The acquirer’s revenue will only reflect the portion needed to cover costs and a normal profit to complete the contract. All the sales margin that was embedded in that deferred revenue is kind of “reset” in the purchase accounting.

This leads to a few important implications:

- Immediate Post-Acquisition Revenue Dip: The acquired company’s GAAP revenue will often drop in the first year after acquisition compared to what it would have been standalone, because the acquirer recognized a smaller deferred revenue balance. In our example, the acquired business’s recognized revenue in 2025 under the new owner is $200K less than it would have been (because $400K vs $800K over two years). This can be a shock if not understood – I’ve seen situations where a buyer had to explain to their investors why the newly acquired SaaS company’s revenue is lower than expected purely due to accounting, not due to losing customers. It’s literally revenue “vanishing into thin air” post-transaction. Rödl & Partner (a global accounting firm) described it well: after an acquisition, the company can only “dissolve a lower contract liability over the remaining term and therefore report lower revenues,” which can lead to negative surprises if stakeholders aren’t aware of the haircut.

- Why the Haircut Happens (Cost Already Incurred): One way to think about it is that the seller had already done the hard work to obtain those contracts (sales commissions paid, marketing, onboarding, etc.), and possibly even incurred upfront costs to deliver (like initial setup). The acquirer is basically picking up mid-stream on these customer relationships. The accounting rules don’t let the acquirer count the full deferred revenue because some of that value was tied to the seller’s efforts and profit margins. For example, if the seller spent money on customer acquisition and implementation, those costs are sunk, and the acquirer doesn’t incur them – so the acquirer shouldn’t recognize revenue associated with recovering those costs. The fair value only includes what the acquirer will spend to fulfill the contract plus a modest profit. In SaaS, fulfilling an ongoing subscription might be relatively cheap (servers, support staff) compared to the contract value, hence the large write-down.

- Contract Liabilities vs. Goodwill: The portion of deferred revenue written down is often effectively rolled into goodwill or intangible assets as part of the purchase price allocation. The buyer paid for the whole business including those customer contracts, but for accounting purposes that extra $400K in our example might end up in goodwill rather than as deferred revenue liability. This is more technical, but the key point is: the haircut doesn’t mean the buyer didn’t value those contracts – it just means the accounting treatment shifts that value out of deferred revenue into other buckets.

All this sounds a bit dreary for a seller with lots of deferred revenue. But there’s some good news on the accounting front (at least under U.S. GAAP):

The New Rule: Deferred Revenue Haircuts (Mostly) Going Away in GAAP

Historically, as described above, GAAP required that deferred revenue be recorded at fair value in an acquisition (resulting in haircuts). However, in late 2021 the Financial Accounting Standards Board issued ASU 2021-08, which changed how acquirers can treat contract assets and liabilities (like deferred revenue) in a business combination. Under the new guidance, if adopted, an acquirer may elect to simply carry over the target’s contract liability balances as is, rather than doing a separate fair value calc. In essence, the acquirer can treat the acquired deferred revenue “as if it had originated the contract”, meaning no haircut – record it at the same remaining amount the seller had. This is a big relief for companies in the software sector. It improves comparability of pre- and post-acquisition revenues and eliminates that weird revenue dip.

To clarify, as of 2022-2023 this new rule started to be adopted widely. If you sell your company to a buyer who has adopted ASU 2021-08 (most public companies and many large private ones likely have by now), they might not apply a deferred revenue haircut at all. In our case study above, the buyer could choose to record the full $800K as deferred revenue on their opening balance sheet and recognize the revenue normally over 2 years, just as you would have. From a founder’s perspective, that’s great because it means the accounting won’t “lose” any of your contracted revenue. This makes your deferred revenue more valuable in SaaS M&A negotiations.

However, a few caveats:

- This is a U.S. GAAP update. If you’re dealing with an international (IFRS) acquirer, note that IFRS rules still require fair value for now. There’s no equivalent widespread IFRS exemption as of 2025. So European or other non-U.S. buyers might still insist on the old treatment (haircut).

- Even under GAAP, the new rule is effectively an election in purchase accounting. Most buyers will take it (why wouldn’t they, it makes life easier), but theoretically they need to have adopted that accounting standard update. It’s worth asking or clarifying.

- If a buyer does not adopt the new guidance, then the old haircut approach still applies and you should be prepared for that discussion.

Bottom line: The deferred revenue haircut is a well-known phenomenon in SaaS M&A. It used to be an automatic reality of any acquisition – something both sides had to account for in their models and deal negotiations. Going forward, new accounting rules can eliminate the haircut for many deals, but not all. As a seller, you should understand which scenario applies, because it can impact how the buyer views your revenue and how you might negotiate the purchase price or deal structure.

Speaking of negotiation, let’s turn to how deferred revenue factors into deal-making and what you can do to maximize value.

Negotiating Deferred Revenue in a Deal: Working Capital and Purchase Price Adjustments

When selling your company, deferred revenue often becomes a hot topic in negotiations between you (the seller) and the buyer. The fundamental issue is this: you’ve collected cash for services the buyer will have to provide after closing. In a typical cash-free, debt-free deal, the seller keeps the cash on hand, and the buyer is essentially saying “I’ll pay you $X for the business, assuming you leave no cash behind.” But if you’ve been paid for future services, should you effectively leave some of that cash for the buyer to cover the costs of delivering those services? Buyers and sellers can have different perspectives on this:

- The Buyer’s view: “We’re taking on a liability – we need to service those prepaid contracts. If you take all the cash that customers paid, we’re out of pocket to deliver the product. We should be compensated for that, either via a lower purchase price or by you leaving some cash in the business.” In other words, buyers may argue that deferred revenue is akin to a debt the company owes (in services). In extreme cases, they might treat deferred revenue like debt dollar-for-dollar in the deal math (this is very buyer-friendly). As one advisory firm notes, the buyer might ask for 100% credit of any pre-paid amounts, especially if treating deferred revenue as debt in the closing adjustment. .

- The Seller’s view: “Those prepaid contracts are part of the business value – they represent committed future revenue and we’ve already done the work to secure them. I shouldn’t be penalized for having upfront cash; that’s part of the deal you’re buying.” Sellers prefer to treat deferred revenue just as normal working capital: you keep the cash, and the deferred revenue is just a liability that the business will work off in due course, with no special price adjustment.

In practice, most deals find a middle ground. Here are three common approaches to deferred revenue in M&A, from most buyer-favorable to most seller-favorable (based on what I’ve seen and what firms like ML&R have observed):

- Treat Deferred Revenue as Debt (Buyer-friendly): In this approach, deferred revenue is excluded from the normal net working capital calculation and instead treated like debt in the purchase price adjustment. The buyer essentially gets a dollar-for-dollar reduction in price or a credit for all deferred revenue. This is quite buyer-favorable (this option is the least common because of how skewed it is). It might be argued for if there are very large long-term deferred revenue balances (since typically long-term obligations wouldn’t count in working capital anyway).

- Include Deferred Revenue in Working Capital (Seller-friendly): Here, deferred revenue is left in the working capital calculation like any other liability, both in setting the target working capital and in measuring it at closing. This means there’s no special adjustment – effectively the buyer is paying for the deferred revenue (and taking the cash benefit). This approach is simple (no extra math), but buyers often resist it in a cash-free deal because they feel they’re not being compensated for the service obligation. One nuance: if your deferred revenue has been growing rapidly, including it in working capital can actually (indirectly) favor the buyer in a peg/true-up mechanism – but that’s an edge case. Generally, this is seen as very seller-friendly.

- Exclude Deferred Revenue but Leave “Cost to Serve” Cash (Balanced): This is a compromise where deferred revenue is excluded from the working capital calc (so not counted as a normal liability for target working capital), but the seller agrees to leave behind a portion of cash in the business to cover the future service costs for those prepaid contracts. How much cash? Often, it’s calculated based on the cost to deliver the remaining obligations, not the full deferred revenue. A common method is to use the inverse of your gross margin (i.e., if your recurring gross margin is 80%, then 20% of the deferred revenue would be left as cash). That ensures the buyer has enough on hand to fulfill the service (pay for support staff, hosting, etc.) until the next renewal, but the seller gets to keep the portion of cash that represents profit. This approach aligns with the fair value concept we discussed earlier (cost to serve + profit). It’s currently a very common treatment in SaaS dealsbecause it feels fair: the buyer isn’t paying for services twice, and the seller isn’t losing the benefit of the upfront cash entirely.

Beyond these, there can be other creative solutions (such as adjusting earn-outs or using escrow to address any customer non-renewal risk, etc.), but these three cover the majority of cases.

Case Study 2 – Negotiating Deferred Revenue in a Sale: DataSyncCo is a SaaS business being acquired in a cash-free deal. It has $7M in cash on the balance sheet and $4.5M in deferred revenue (mostly annual prepayments for the year ahead).

The buyer and seller negotiate the following: They exclude deferred revenue from the target working capital, but they agree that $900K of cash will remain in the company at closing specifically to cover the cost of servicing those prepaid contracts (DataSyncCo’s gross margin is ~80%, so $900K is roughly 20% of $4.5M). The remaining $6.1M of cash is paid out to the seller. In effect, the buyer gets comfort that the customer obligations are funded, and the seller still walks away with the majority of the prepaid cash. Both sides feel this is equitable. If the seller had not understood this concept, the buyer’s initial stance was to reduce the purchase price by the full $4.5M – a huge value difference! By using the cost-to-serve approach, they avoided a “double count” hit to valuation.

The key takeaway is to anticipate this discussion and shape the narrative. As a founder, with your advisors, you should model out what your deferred revenue and cash will look like at closing and have a position on how to handle it. When both parties understand the mechanics, it often comes down to a logical negotiation of how much of the prepaid amounts should effectively be passed on to the buyer versus kept by the seller.

Strategies for SaaS Sellers to Maximize Value

Deferred revenue doesn’t have to derail your SaaS exit plans. Here are several strategies and tips to ensure you maximize your company’s value:

1. Educate Yourself Early: Simply by reading this far, you’re ahead of many first-time sellers. Be aware that if you have large deferred revenue balances, buyers will definitely take notice. Understanding the basics means you won’t be caught off guard. You can also engage your CFO or a SaaS-savvy accountant to quantify your deferred revenue (current vs long-term) and even estimate what a fair value write-down might look like. Knowledge of deferred revenue in SaaS M&A means you’ll negotiate more confidently if you know the ballpark impact.

2. Highlight Quality of Revenue (Not Just Quantity): Smart buyers care about the quality of your revenue. If much of your revenue is prepaid, emphasize the positives: it indicates customer commitment and strong cash flow. Make sure to communicate metrics like RPO, renewal rates, and gross margins. High gross margins mean the cost to fulfill those deferred obligations is low, which could mitigate a buyer’s concern (and under new GAAP rules, could be a non-issue for revenue recognition). If you have stellar retention and low churn, point out that the deferred revenue truly will convert to actual revenue with very little risk. This can justify that the prepaid amounts are solid value, not a liability to be deeply discounted.

3. Manage and Present Your Financials Cleanly: Before going to market, ensure your financial statements cleanly reflect deferred revenue under GAAP. This may involve implementing proper revenue recognition tools or processes (many startups move from cash-basis to accrual for this reason). Be ready to provide a deferred revenue schedule that shows how it rolls off into revenue in future periods. This level of transparency builds trust. Also, be prepared to explain your billing practices (monthly vs annual vs multi-year) and any trends in deferred revenue. For instance, if you recently started selling more multi-year deals, the deferred revenue spike is a sign of growth, not a red flag – but you need to articulate that story.

4. Leverage the New Accounting Standards: If you suspect the buyer may not be up-to-date on ASU 2021-08, it is worth bringing up. This is a bit tactical, but if during negotiations a buyer is harping on the deferred revenue haircut issue (“we’re going to lose X revenue due to write-down”), you or your advisors can point out that under updated GAAP they might not have to lose any revenue at all. This doesn’t directly put cash in your pocket, but it undermines a potential argument for lowering valuation. Essentially, don’t let an uninformed buyer double-count a problem – if the accounting standards offer a solution, make sure it’s considered. (Of course, this depends on the buyer’s accounting policies, but it’s part of the conversation.)

5. Negotiate Working Capital Wisely: As discussed in the prior section, structure the deal’s working capital adjustment to your advantage (or at least fairly). Push for either including deferred revenue in the normal working capital or the compromise of leaving only cost-to-serve cash. Avoid agreeing to treat deferred revenue as debt or a full reduction in price, unless it’s absolutely unavoidable. This is where a good M&A advisor (like our team at FE International) earns their keep – by knowing market norms and pushing back on aggressive asks. Remember the Allied Advisers note: if deferred revenue is not counted in working capital, it can lead to a downward purchase price adjustment. So don’t give that up without a fight or compensation elsewhere.

6. Time Your Deal (If Possible) with Billing Cycles: This is a subtle point – and often you can’t perfectly time an acquisition – but be mindful of your billing cycles. If a huge chunk of your customers all renew and pay annually on January 1, and you close your sale on January 2, you’ll have a giant deferred revenue liability and no offsetting AR or anything. Some sellers in that position might negotiate that the deal effective date be just before the big billing, or ensure the working capital adjustment accounts for the surge. You probably won’t delay growth just for optics, but it’s worth thinking through the timing. The goal is to avoid scenarios where, say, you have unusual short-term spikes in deferred revenue that a buyer could point to in order to retrade the deal economics.

7. Use Case Studies and Past Deal Precedents: If a buyer is being tough, it can help to reference how similar deals handled it (without breaching any confidential info of course). For example, you might say, “Look, other acquirers in our industry have been comfortable simply carrying over deferred revenue because they know it’s high-margin. And most private equity deals right now just leave a bit of cash for cost-to-serve – that’s become the norm. We’re not asking for something unusual.” This frames your ask as reasonable. If you’re working with an M&A advisor, they can provide anonymized examples of recent transactions (we do this often at FE International to show what’s “market”).

8. Prepare for Post-Acquisition Integration: Lastly, if you do close the deal, be prepared for the accounting transition. If the buyer does impose a deferred revenue haircut, you might need to explain to your team (and maybe your earn-out trackers, if you have an earn-out) that the reported revenue will look different. Internally, focus on metrics like ARR and RPO which aren’t affected by purchase accounting. Many acquirers will also present non-GAAP pro forma figures that add back the written-down deferred revenue to show the business’s true growth. Understanding this will help you set appropriate targets if you stay on with the company post-acquisition. And if no haircut is applied (thanks to the new rules), there will be one less integration headache.

If you're still in growth mode but want to stay exit-ready, consider building financial visibility early. FE Capital, our investor outreach and fundraising platform, helps SaaS founders organize key metrics, benchmark valuations, and prepare the kind of clean financial story that both investors and future acquirers want to see. Whether you're raising now or just getting structured, having that clarity makes all the difference when the right opportunity comes.

Conclusion: Turning a Complex Accounting Topic into a Win

Deferred revenue in SaaS is a classic example of an accounting concept that has real business and deal implications. We’ve covered a lot: from the basics of recognizing revenue, to the intricacies of multi-year contracts and remaining performance obligations (RPO), through the maze of acquisition accounting and negotiations. The key points to remember are:

- Deferred revenue = cash received for services you owe. In revenue recognition in SaaSit’s recorded as a liability until you deliver. This is normal (and good!) in SaaS, but requires accrual accounting to handle properly.

- Accrual vs Cash accounting: Under accrual you recognize revenue as earned, hence deferred revenue exists; this gives a clearer financial picture.

- Multi-year deals boost deferred revenue and create backlog; RPO captures the full picture of future contracted revenue. These are strong indicators of your company’s health if managed well.

- Acquisition accounting historically required writing down deferred revenue to fair value, resulting in a revenue haircut for the acquirer. This could significantly lower reported revenue post-deal. But new GAAP rules (ASU 2021-08) now allow carrying it over with no haircut, eliminating that distortion (check what your potential buyer will do).

- Negotiation: Deferred revenue will likely be a negotiated item in the purchase price or closing adjustments. Aim for a fair solution – often leaving just the cost to fulfill obligations, not the entire deferred amount. Be wary of any attempt to treat it 100% like debt unless offset elsewhere.

- Strategies to maximize value: Know the rules, present your metrics (RPO, margins, retention) to bolster the case that your deferred revenue is high-quality, and use expert advice to navigate working capital terms

As an M&A advisor, our role is often to bridge the gap between accounting theory and real-world impact. My advice to founders is: don’t shy away from deferred revenue – manage it and message it strategically. Buyers ultimately want a growing, healthy SaaS business; deferred revenue is part of that story. By being proactive, you can turn what might seem like a “technical headache” into a demonstration of your business’s strength (e.g., lots of customers prepaid because they trust your service!).

If you’re a SaaS founder considering your exit strategy and all this still feels overwhelming, that’s completely normal. These are complex issues, and the stakes are high. At FE International, we specialize in helping SaaS companies navigate every aspect of the sale process – including tricky accounting items like deferred revenue. We can help you present your financials in the best light, set appropriate expectations with buyers, and negotiate terms that protect the value you’ve built.

.png)